Methanol

When you’re making spirits and you start with a mash made purely from sugar or molasses, you don’t have to worry much about methanol. Almost no methanol forms in this type of wash, meaning it’s one of the safer starting points for distilling at home or in the distillery.

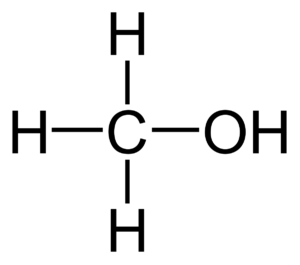

But if you use ingredients like fruits or grains, things are a little different. Fruits contain pectin—a kind of natural thickener—while grains have cellulose. These are called polysaccharides, which are just long chains of sugar molecules. When yeast gets to work during fermentation (that’s when sugar turns into alcohol), these complex sugars can lead to small amounts of methanol being created.

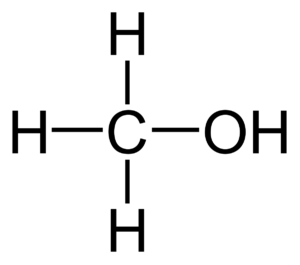

It’s important to understand that methanol isn’t made during the distillation process. It forms while your mash is fermenting. By itself, methanol is not extremely toxic, but your liver tries to break it down and ends up making even worse stuff—formaldehyde and formic acid. Those chemicals can be very dangerous. One of the most serious risks is blindness, because these byproducts attack your optic nerves.

If someone accidentally drinks methanol, doctors actually give them ethanol (regular drinking alcohol) as an antidote. This is because the liver processes ethanol first, so it buys time for the body to clear the methanol more slowly, reducing damage.

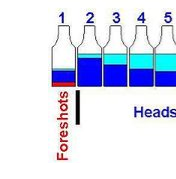

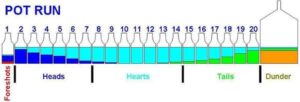

During distillation, methanol is one of the first things to come off because it has a lower boiling point than ethanol. Methanol boils at about 147°F (64°C), while ethanol boils at 173°F (78°C). When you gently heat up your still, methanol evaporates first. That’s why, as a rule, we always collect and discard the “foreshots,” which are the very first liquid to come out during a run. The foreshots often have a slightly oily appearance on top of the wash and tend to taste bitter, almost like chemicals.

These foreshots represent only a small fraction of your batch—about 3% at the start of your distilling run. In traditional distilling circles, nobody drinks this part. Moonshiners and professional distillers alike know to throw the foreshots away. This brings peace of mind, especially if you’re using fruit or grain mashes.

After you’ve removed the methanol with the foreshots, some other light compounds with low boiling points also need to go. These include things like acetone (smells like nail polish remover), acetaldehyde (which smells sharp and is also called ethanal), and acetate. These chemicals are all grouped together as “fusil oils” and come out early in the run because they, too, boil at temperatures below ethanol. Not only do they taste and smell bad, but they’re hard on your body and can lead to nasty hangovers.

Once you’re done collecting your main body of clean ethanol, there might still be a few unwanted chemicals left with even higher boiling points than alcohol. These come out at the very end of the run. They’re usually present in tiny amounts, but if you want an extra-pure spirit, you can remove these by filtering your finished product. Activated carbon filters, for example, are often used to polish vodka or clear spirits.

So, to sum up: if you want safe, great-tasting spirits, always discard the foreshots at the start of your run—especially if you’re using fruit or grain. This simple step gets rid of most of the methanol and other yucky compounds, leaving behind the good stuff for you to enjoy!

Blind Man

First Top Layer – Foreshots = Discard !!!

The Very Top Layer

Hydrogen Sulfide – First Order of Business

Hydrogen Sulfide – The First Thing Every Distiller Needs to Know

Whenever you make spirits from grains or fruits—whether you’re making whiskey, vodka, rum, or brandy—there’s always some hydrogen sulfide produced during fermentation and distillation. Hydrogen sulfide is a chemical with a very strong, unpleasant smell; it’s that classic “rotten eggs” odor you might remember from school chemistry experiments.

Now, this is more than just a bad smell. Hydrogen sulfide is actually quite dangerous. Even in very small amounts, it is almost as poisonous as hydrogen cyanide! If even a small amount of this gas ends up in your finished spirit, it will ruin the taste and make your product unsafe. Here’s why: at low levels, you can smell it and notice something’s wrong. But the danger is that, as concentrations rise, hydrogen sulfide can numb your nose so you stop smelling it—right when it’s the most dangerous. This happens because it is actually a nerve toxin, and when enough builds up, your nose is ‘anesthetized.’ At that point, you won’t notice how much has accumulated, which is why we have to be extra careful.

The good news is: most fermentation only makes very small amounts of hydrogen sulfide. But even those must be dealt with. How do we handle it?

We use copper. Copper is an essential part of safe distilling. When hydrogen sulfide comes into contact with copper, the two react. The hydrogen sulfide chemically bonds with copper, forming a blue-green compound called copper sulfate (you’ll see it as blue stains on the copper after runs). At the same time, the copper releases a harmless hydrogen gas. Basically, the copper ‘traps’ the stinky and dangerous hydrogen sulfide, cleaning up your spirit.

That’s why, even if your still is made of stainless steel—which doesn’t do this chemical cleaning—you should always add a piece of copper inside your still. Many distillers use copper mesh or copper pipe in their vapor path. This step ensures that any hydrogen sulfide made during your distillation is safely absorbed and doesn’t end up in your final product.

BUT—don’t forget! After every distillation, those copper parts need to be cleaned really well. The copper sulfate left behind is also a poison and must be removed before the next run. Scrub and rinse your copper pieces thoroughly, and always follow the cleaning instructions specific for both copper and stainless steel surfaces. Keeping your equipment clean keeps your spirits safe and tasty.

So remember: hydrogen sulfide is always produced, it’s always dangerous, and copper is the reliable way to remove it. Clean your copper parts every time. This is one of the first and most important lessons in distilling safely and making spirits you’ll be proud of.

First Stage – Foreshots = Discard

First Stage Objective: Understanding and Removing the Foreshots

When we begin the distillation process, our very first and most important task is to separate and discard what we call the “foreshots.” These are the first liquids that come out of your still, and they contain compounds and oils that are not just undesirable in taste, but can also be dangerous to your health. The foreshots are comprised of low-boiling-point substances—mostly harmful alcohols and solvents—that evaporate before pure ethanol (drinking alcohol) does.

The primary goal at this stage is to remove the “bad oils,” sometimes called fusel oils or heads. These bad oils have boiling points lower than alcohol (Ethanol boils at 78°C or 172°F at sea level). These lighter, volatile compounds include things like methanol (wood alcohol) and acetone, both of which can be harmful if consumed, even in small amounts.

Bringing Up the Heat: How to Handle the Mash

To achieve this, you’ll want to slowly preheat your mash (the fermented mixture that you are distilling) up to about 56.5°C (134°F), which helps start releasing those lighter compounds. It’s important to not rush. Hold this temperature for about five minutes to give those lighter, harmful substances a chance to evaporate before the main alcohol starts to come over.

After this holding period, begin to raise the temperature very gradually, up to just below the boiling point of ethanol. For a small batch—let’s say a couple of gallons—this slow ramp-up should take at least 10 minutes, but 15 minutes is even better if you want to be thorough. Taking it slowly allows ALL the undesired light compounds time to leave the mash and collect as foreshots. If you go too quickly, you risk leaving some of these harmful substances behind, and they could end up in your finished spirit.

Typically, at this stage, you can expect to collect around three-quarters of an ounce of foreshots per gallon of mash. It is extremely important that you discard everything that comes off during this early phase, because these first drops—the “heads”—are NOT safe to drink.

Visual and Sensory Clues: What Do the Foreshots Look and Feel Like?

Once your mash reaches roughly 135°F, you can take off the lid of your mash pot and actually observe what’s happening. You might see a slick, shiny layer floating on top of the mash. This is made up of some of the lighter, volatile compounds, like methanol and acetone. If you gently touch this layer, you’ll notice that it feels slippery, even a bit oily between your finger and thumb. These are all clues that you are dealing with the unwanted foreshots.

Going ‘Low and Slow’: Why Patience Matters

Between 145°F and 155°F, methanol (a particularly dangerous alcohol) will start to slowly vaporize and evaporate. Again, patience pays off here: Spend 10 to 15 minutes very slowly increasing the temperature through this key evaporation window. If you were to rush this part and raise the temperature to this window in just a few minutes, there would still be dangerous methanol left in your pot and possibly in your end product.

As you progress through this temperature range, you will start seeing liquid dripping from your condenser. Collect this separately—DO NOT drink or use it for flavoring. You can identify some of these foreshots by smell (they tend to be sharp, solvent-like, and unpleasant) as well as by testing with fire.

A Simple Test: Identifying Bad Oils vs. Good Alcohol

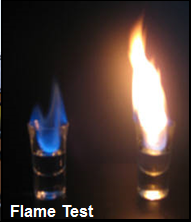

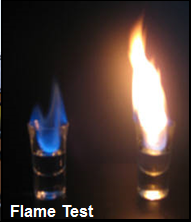

One way to check if you are past the harmful foreshots is the flame test. Take a few drops of the distillate and put them on a non-flammable surface, like a metal spoon or a piece of glass. Light it with a match:

- If it burns yellow, that’s a sign you are still dealing with the bad, light oils (foreshots).

- Once the flame turns blue, you are starting to collect pure ethanol (drinking alcohol), known as the “hearts” in distilling.

This simple test can help you visually and safely tell when it’s time to start collecting your spirit for drinking.

Common Foreshot Compounds and Their Boiling Points

- Acetone: Boils at 134°F (56.5°C). Very light and will evaporate quickly as the temperature rises.

- Methanol: Boils at 148.5°F (64°C). Extremely toxic if consumed; in the body, it turns into formaldehyde and formic acid, which can attack nerves and even cause blindness in large amounts.

- Ethyl Acetate: Boils at 171°F (77.1°C). Adds unpleasant flavors and should be avoided.

- Ethanol (Ethyl Alcohol): Boils at 173.5°F (78°C). This is the alcohol we want for consumption (assuming we’re following all legal requirements).

Summary: Distilling is all about patience and care, especially at the beginning. Take your time heating up the mash, watch for the visual and tactile clues on the surface, and be very thorough in collecting and discarding those early foreshots. This attention to detail at the start is critical for making sure your spirit is safe, clean, and of high quality. As a master distiller, I can’t stress enough: never be tempted to keep or use the foreshots—your health and the quality of your spirits depend on it.

Methanol

When you’re making spirits and you start with a mash made purely from sugar or molasses, you don’t have to worry much about methanol. Almost no methanol forms in this type of wash, meaning it’s one of the safer starting points for distilling at home or in the distillery.

But if you use ingredients like fruits or grains, things are a little different. Fruits contain pectin—a kind of natural thickener—while grains have cellulose. These are called polysaccharides, which are just long chains of sugar molecules. When yeast gets to work during fermentation (that’s when sugar turns into alcohol), these complex sugars can lead to small amounts of methanol being created.

It’s important to understand that methanol isn’t made during the distillation process. It forms while your mash is fermenting. By itself, methanol is not extremely toxic, but your liver tries to break it down and ends up making even worse stuff—formaldehyde and formic acid. Those chemicals can be very dangerous. One of the most serious risks is blindness, because these byproducts attack your optic nerves.

If someone accidentally drinks methanol, doctors actually give them ethanol (regular drinking alcohol) as an antidote. This is because the liver processes ethanol first, so it buys time for the body to clear the methanol more slowly, reducing damage.

During distillation, methanol is one of the first things to come off because it has a lower boiling point than ethanol. Methanol boils at about 147°F (64°C), while ethanol boils at 173°F (78°C). When you gently heat up your still, methanol evaporates first. That’s why, as a rule, we always collect and discard the “foreshots,” which are the very first liquid to come out during a run. The foreshots often have a slightly oily appearance on top of the wash and tend to taste bitter, almost like chemicals.

These foreshots represent only a small fraction of your batch—about 3% at the start of your distilling run. In traditional distilling circles, nobody drinks this part. Moonshiners and professional distillers alike know to throw the foreshots away. This brings peace of mind, especially if you’re using fruit or grain mashes.

After you’ve removed the methanol with the foreshots, some other light compounds with low boiling points also need to go. These include things like acetone (smells like nail polish remover), acetaldehyde (which smells sharp and is also called ethanal), and acetate. These chemicals are all grouped together as “fusil oils” and come out early in the run because they, too, boil at temperatures below ethanol. Not only do they taste and smell bad, but they’re hard on your body and can lead to nasty hangovers.

Once you’re done collecting your main body of clean ethanol, there might still be a few unwanted chemicals left with even higher boiling points than alcohol. These come out at the very end of the run. They’re usually present in tiny amounts, but if you want an extra-pure spirit, you can remove these by filtering your finished product. Activated carbon filters, for example, are often used to polish vodka or clear spirits.

So, to sum up: if you want safe, great-tasting spirits, always discard the foreshots at the start of your run—especially if you’re using fruit or grain. This simple step gets rid of most of the methanol and other yucky compounds, leaving behind the good stuff for you to enjoy!

Blind Man